In this post, I’m sharing what I’ve been learning about AI in language teaching, not just the theory from my course but also how I’ve started experimenting with it in real ESOL classrooms. From marking and feedback to accessibility and listening support, I’ve been exploring where these tools actually make a difference and where they don’t. If you’re curious about how teaching experience can shape the way we design digital learning, I hope this reflection gives you a few ideas of your own.

Credit: thisisengineering on Pexels

Crossing a Threshold with AI in Language Teaching

I’ve reached a small but important milestone: I’ve now completed the online learning phase of my digital learning design course. In my last post, I reflected on learner journey and LX design and how it shaped my early approach to course planning.

Since then, I’ve moved through Module 4, focused on Artificial Intelligence, and officially chosen the Instructional Design pathway for my assessment project.

It feels like I’m crossing a threshold. The course content is now less about foundational knowledge and more about experimentation, design decisions, and how new tools might support real learners. At the same time, my teaching year has begun again. I’m gathering data from learner surveys and diagnostic assessments, and this practical insight is feeding directly into my course project. I’ve also started building my first course in Canvas, exploring how discussion tools might support more authentic writing tasks.

This post is a reflection on what I’ve learned about AI, how I’ve started using it, and how it’s shaping my thinking about teaching, inclusion, listening, and instructional design.

Rethinking AI in Language Teaching Beyond the Hype

Module 4 opened with a big-picture view of Artificial Intelligence, how it works, what terms like natural language processing and machine learning really mean, and how AI’s affordances and limitations intersect with education. It also explored ethics, data protection, and some of the myths that often dominate public conversations.

One thing that surprised me was learning that many AI systems are modelled on how humans think, something I’d never stopped to consider. I also discovered that “artificial general intelligence,” the idea of AI surpassing human intelligence, is still far off despite the dramatic headlines.

This shift in perspective helped me see AI more clearly as a set of tools, not a futuristic threat. At its best, AI analyses huge amounts of data, identifies patterns, and generates insights far faster than we ever could. But it still relies on human expertise to make sense of those insights, apply them meaningfully, and ensure they’re used ethically.

The fact that AI is significant enough to warrant an entire module in my course made me rethink its place in my own teaching. I’m now considering running a session to introduce my learners to AI tools for language learning, ideally using ready-made materials such as the Cambridge GenAI Idea Pack for English Language Teachers and the British Council AI Activities and Resources for English Language Teachers, both of which offer excellent ideas for integrating AI into lessons. Introducing these tools could help learners see AI not as something abstract or intimidating, but as a practical support for vocabulary building, practice, and independent study beyond the classroom.

AI in Language Teaching Tools for ESOL Classrooms

At a recent staff development session, we explored a range of AI-powered tools designed to support teaching. The first session was about differentiation and how AI can help. A few tools were suggested, including MagicSchool, Curipod, Thinglink, and Book Creator.

I’ve found that MagicSchool operates in the same space as Teachermatic. Both are designed as quick, safe, education-aligned tools to save teachers time with planning and admin. If you’re a classroom teacher in a mainstream subject in a school, they make sense.

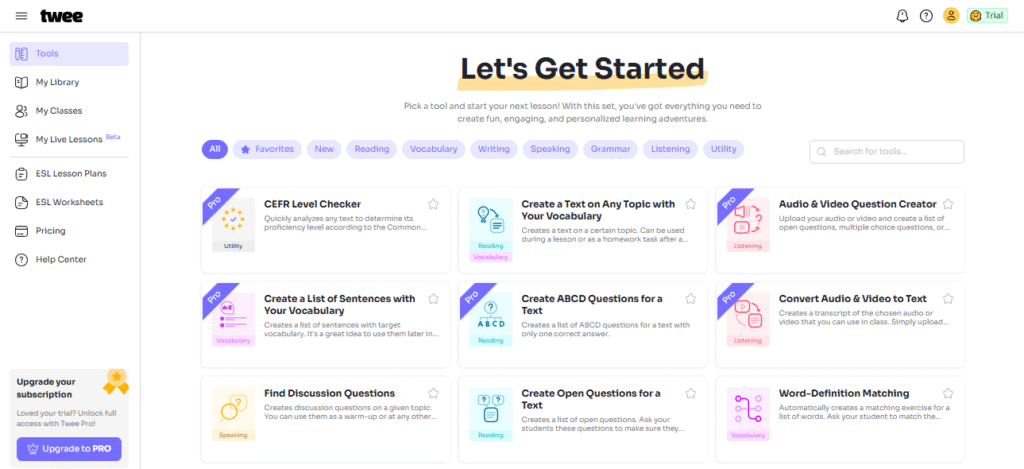

For my own context, though, I haven’t really found these useful. ESOL has its own rhythms, methodologies, and challenges, and the generic tools haven’t always addressed those. I’ve discovered that Twee does a much better job. It’s specialised for language teaching, offers CEFR-aligned tools, and builds activities around familiar methodologies like PPP (Presentation–Practice–Production). If I want broader flexibility, ChatGPT still offers the most creative potential, as long as I’m prepared to spend time crafting effective prompts.

Other tools piqued my curiosity too. Curipod generates interactive slides with polls and questions to drive active learning, while Thinglink allows you to layer language tasks and audio on top of images, grounding vocabulary in real-world contexts like shops or workplaces. These feel like tools that could genuinely enrich language learning rather than just automate existing processes.

Putting AI into Practice

It’s one thing to learn about AI in theory, but the real insights come from trying it out. Over the past few months, I’ve been experimenting with how AI in language teaching could support my classroom practice, sometimes with success and sometimes less so.

I decided to experiment with AI for diagnostic writing assessment to see if it had any real potential to save time and deliver more tailored feedback. I wanted to see if ChatGPT could evaluate student scripts against uploaded rubrics and provide feedback. The results were mixed. Early attempts were inconsistent, and while iteration improved the output, it was clear that significant calibration, perhaps even a custom GPT, would be needed for reliable assessment. It’s an idea I may return to, but for now, it reminded me how important human moderation and judgment still are.

Other experiments were more immediately useful. I’ve used AI to help draft end-of-term student reports by training it on anonymised examples I’d written and giving it strict parameters. The result? What used to take me two days now takes a few hours, and the reports are more varied, consistent, and personalised. This experience taught me that AI isn’t about doing less work; it’s about shifting where I focus my energy.

Inclusive Learning Through AI

One of the most valuable outcomes of Module 4 was how it reframed my thinking about accessibility. My ESOL learners don’t just face language barriers; many also experience overlapping challenges, including low literacy, hearing loss, trauma, or long work hours. These complexities shape how and when learning happens.

AI can play a powerful role here if it’s used thoughtfully. Tools like text-to-speech can help pre-literacy learners connect sound to print, and they’re also valuable for pronunciation practice with learners at the A1–A2 level who are building towards A2–B1. Live transcription apps such as Google Live Transcribe can make spoken input more accessible for learners with hearing loss, and they can also help others at similar levels notice features of natural speech such as connected speech and rhythm.

The more I thought about it, the clearer it became: designing for the most in-need learners often improves learning for everyone. A barrier-aware approach that integrates assistive technology, multi-modal delivery, and inclusive pedagogy benefits the whole class.

I’d like to build on this by running a small pilot in my classroom to test how real-time speech-to-text or text-to-speech tools could support my learners. It might be as simple as integrating one tool into a lesson and reflecting on the results, but it’s a step toward making technology part of a more personalised access plan.

Designing for Listening with AI

Alongside exploring AI, I’ve also been thinking more deeply about how to support my learners with listening, a skill many of them find the hardest to master. Research by specialists like Richard Cauldwell and Sheila Thorn shows that most learners don’t struggle with vocabulary, but with decoding how words sound in real, fast speech. Traditional comprehension tasks don’t help much, because they test listening rather than teach it.

This has led me to explore new approaches that focus on the “messy” reality of spoken English, including weak forms, linking, reductions, and other features of connected speech. I’m interested in sequencing lessons so that students build awareness of these features first, before focusing on phonemes or individual sounds. This “real first, tidy later” approach, often framed as a Test–Teach–Test cycle, feels like a more purposeful way to tackle listening barriers. It’s an area I want to keep developing, and one that will shape how I think about lesson design and learner support in future projects.

Bridging ESOL and Instructional Design with AI

Working in ESOL has shaped how I approach technology adoption. Teachers in this field are used to building understanding from zero, designing for wide ability ranges, and constantly balancing clarity with cognitive load. They’re also used to embedding multimodal strategies, combining text, visuals, audio, and interaction to make meaning accessible.

These habits transfer naturally to instructional design. They remind me that technology on its own is not a solution; its impact depends on how well it’s woven into the pedagogy. A tool is only as good as the design decisions behind it.

My experiments with AI in language teaching so far, from marking and feedback to accessibility support, have reinforced a few key lessons:

- AI is most powerful when it complements the expertise of teachers and learning designers, rather than attempting to replace them.

- It can dramatically reduce the time spent on repetitive tasks, freeing up space for deeper, more creative work.

- Focusing on the learners with the biggest barriers leads to better experiences for everyone.

- Small-scale classroom experiments can yield meaningful insights, even without formal research time or funding.

Designing Future Learning with AI

As I move into the next stage of my course, my focus will shift from exploration to creation. I plan to explore more interactive tools, including Thinglink, Genially, H5P, and PowerPoint, to expand my digital design toolkit. I also want to deepen my skills with authoring tools like Adapt and Articulate Rise, which will underpin the design of my final project: an English for Childcare course at CEFR A2–B1 level.

I’m also curious to keep exploring AI in assessment. Once I’ve finished marking my current set of speaking and writing diagnostics, I may use AI to analyse the same scripts and compare the results to my own. This could provide new insights into validity, reliability, and workload reduction, and perhaps pave the way for more automated, scalable approaches in the future.

How Can AI Support Inclusion in Language Teaching?

AI can support inclusion in language teaching by making learning more accessible and personalised. Tools such as text-to-speech, live transcription, and adaptive feedback systems can remove barriers for learners with low literacy, hearing loss, or limited study time. They also create opportunities for differentiated practice and independent learning, helping students with different needs progress at their own pace.

A New Stage in the Journey

Completing this phase of the course has been more than just a box to be checked. It’s changed how I view AI in language teaching, not as a distant technology, but as a set of tools that can make learning more accessible, efficient, and creative. It’s helped me reflect on how my ESOL background shapes my design decisions and how inclusive, learner-centred thinking should guide every new tool I try.

I know I’m only at the beginning. There’s still a lot to learn, test, and refine. But I feel more confident now, not because I have all the answers, but because I know how to keep moving forward. As I start building my first course prototype, those questions will guide every decision I make.

Reflection question: If you’re an educator exploring AI in language teaching, where do you think it could help you most? Could it reduce your workload, support inclusion, or enrich learning experiences? And how might your existing teaching instincts shape the way you design with it?

If you’d like to explore how my thinking has developed, you can also read my reflections on learning theories and visual design, which laid the groundwork for this stage of my course.